July 16, 2025

Dispirited Away: In the wrong hands, ‘Ghiblified’ genAI images erode ethos, empathy, and our very humanity

An art historian who grew up inside Pixar Studios reflects on what we lose when art once rendered through deliberate labor and deep care can be reproduced in seconds — and weaponized just as quickly.

In March, an AI-generated image of an ICE officer detaining Virginia Basora-Gonzalez, an alleged undocumented immigrant, went viral.

Shared by the White House’s official X account, the “Ghiblified” image — generated in the signature style of Japanese animation house Studio Ghibli — mimicked the visual warmth of the worlds enlivened by studio co-founder and filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki. But layered atop actual photos from the arrest, with Basora-Gonzalez’s arms shackled behind her and face twisted in anguish, a headline proclaimed: “Fentanyl Dealer Arrested.” As the soft pastels bare their teeth, we are forced to confront a harsh reality: What do we lose when nostalgia is weaponized to obscure today’s rise of state-sanctioned violence? And how do we recognize the value of art in a digital age when emotion can be evoked without care, labor, or authorship?

On March 25, 2025, OpenAI released its 4o Image Generation model, capable of producing highly detailed, stylized images from text prompts with seemingly unrestricted copyright filters. Users flocked to “Ghiblify” everything from smiling portraits with pets and canonical memes to politically charged moments, like the moment George Bush was informed of the 9/11 attacks.

In an increasingly disconnected world, these images move us not because they are authentic, but because they feel familiar.

In the late 1990s, my father worked as a designer at Pixar Animation Studios. On special Saturdays, I would accompany him on-site in Emeryville, California, riding my Razor scooter through long, empty corridors. I’d peer into the office of John Lasseter, then Pixar’s chief creative officer, marveling at shelves overflowing with Pixar and Ghibli figurines, and framed photos of Lasseter grinning alongside Miyazaki. Around that time, I watched some of Miyazaki’s most formative films, growing up alongside his strong, sensitive female protagonists and seeing my story reflected in theirs.

I watched Chihiro cross into the dream world of Spirited Away, beginning a journey from childhood innocence toward a new identity shaped by hardship, bravery, and unexpected friendships. On the ride home from Pixar at night, I would gaze out the car window just like Chihiro on that near-silent yet weighty train ride, moving through new spaces and experiences I didn’t yet understand. Unbeknownst to me, this was a transformative moment for animation itself, when Ghibli films were being widely distributed in the U.S. for the first time.

Unlike most contemporary animation studios, Studio Ghibli takes a traditional approach to animation, hand-drawing every frame. Their films are fundamentally two-dimensional, using minimal CGI. This meticulous, analog process imbues each scene with a distinct stillness, what the Japanese call ma, or emptiness. Animator Eiji Yamamori famously spent 15 months animating a single four-second crowd scene in The Wind Rises (2013). This level of care is also palpable in My Neighbor Totoro (1998), when sisters Satsuki and Mei splash in puddles and watch toads croak while waiting for the bus under a heavy rain.

This deliberate resistance to constant motion — an invitation to sit in stillness with our feelings — is what makes Miyazaki’s films so magical: moments of pause that allow emotional depth to take root.

For Miyazaki, who grew up during World War II, these moments of respite underline his films’ consideration for the destructive impact of industrialization on the natural world. Ironically, using generative AI, an egregious resource-intensive technology, to create images in Miyazaki’s style goes against the philosophy he dedicated his life to defending. In a now-viral video from 2016, he described AI-generated art as an “insult to life itself.”

Hand-drawn labor, attention to ma, and careful storytelling elevate Miyazaki’s films from reproducible aesthetics into masterful acts of devotion. The viral image of an ICE officer detaining Virginia Basora-Gonzalez, sobbing in cuffs, may evoke the tender moment from Spirited Away when Chihiro quietly weeps into the onigiri Haku offers her — a moment rooted in empathy and emotional truth. But in the hands of power, these tools are used to aestheticize harm and rewrite the story of who deserves compassion.

Miyazaki’s stillness offers a tranquil refuge from humankind’s destructive, ego-driven hunger for power and control. By contrast, AI-generated images — especially those disseminated by authoritarian figures — flatten violence into spectacle. They shift blame from the oppressive systems to the individuals struggling to survive them, casting state violence as order and civil unrest as chaos. This isn’t ma; it’s manipulation.

As we become increasingly dependent on generative tools and numb to their quiet erasures, gaining literacy around how these systems work and shape what we feel becomes more important than ever.

Technology is a flawed reflection of its creators, shaped by coded biases that echo and influence our interactions with the world. The danger is not in the tool itself, but in how it’s used: who holds the blade, and what they choose to cut away. As my father, a designer, reflected on what this might mean for the next generation of creatives, he told me, “It’s a new tool with a lot of potential. When used correctly, it can offer new insights, speed up processes, and open new variables. But ultimately, it illustrates the importance of human designers. At the end of the day, it comes down to your eye and intuition, and what resonates on a human level.”

Watching Miyazaki films as an adult collapses the distance between my childhood self — the version of me who was frightened by No-Face’s search for identity and the thought of leading an independent life — and my adult self, who has since faced those character-building lessons head-on. Still, part of me aches for that innocent version, who had yet to cross the bridge into the dream world.

The author during a weekend visit to Pixar Animation Studios, 2002.

There’s a word in Portuguese, saudade, that captures this feeling. It transcends language, conveying a deep, aching longing for a time and a place that only exists in memory. Saudade isn’t a style that can be reproduced; it takes shape through the joys and heartbreaks of lived experience. It traces the throughline between a protagonist’s coming-of-age and our own remembered selves, something no algorithm can replicate. And yet, I expect, we will continue to ask it to.

The Studio Ghibli AI trend ended as quickly as it began. Search interest for the meme tool went from zero to 100 in just one week following the model’s late-March release, but it quickly tapered off by early-April. While the trend itself was fleeting, the technologies and values they encode will continue to shape our cultural and political landscapes. These Ghibli-style images reflect a collective longing for connection, filtered through nostalgia. But the cost of mimicking meaning is the erasure of the very hand, labor, and ethos that once gave the original its soul.

As I listen to the opening phrase of “One Summer Day,” the theme from Spirited Away composed by Joe Hisaishi, who scored all but one of Miyazaki’s films, I’m reminded of every past version of myself, and of Studio Ghibli’s female heroes, who taught me that our greatest power often lies in our capacity to hold softness. What lingers is not just the style — though the studio’s aesthetic comes as close to mastery as one can get — but the soul: the brave smile through tears, the pauses for childlike play, and the care etched into every frame. In these deeply human connections, shaped by memory, vulnerability, and care, art finds its meaning. Not rendered, but remembered: lived, felt, and carried in the whisper of the heart.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Sigourney Schultz

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Dylan Fugel|Analysis

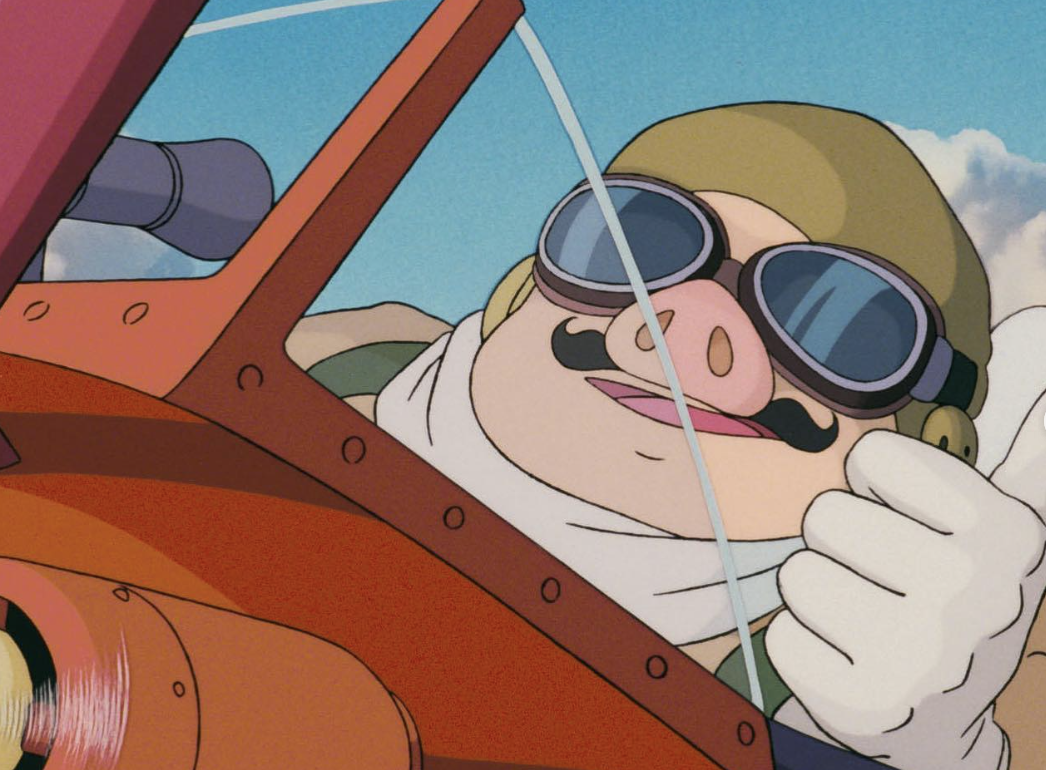

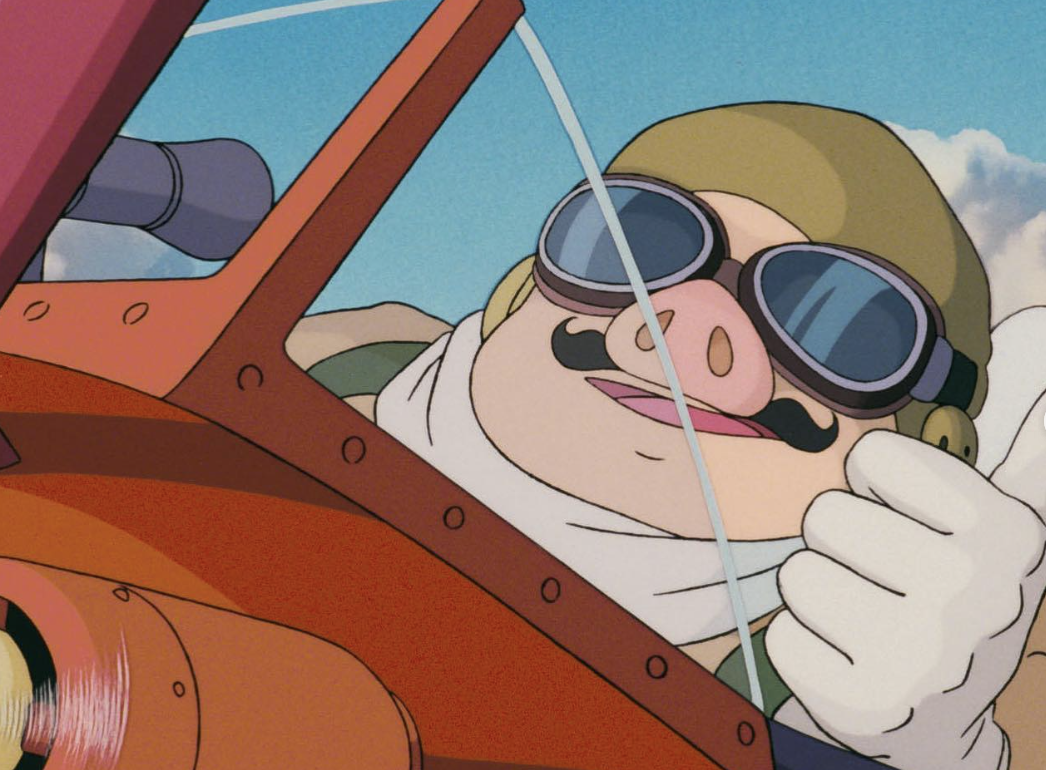

“I’d rather be a pig”: Amid fascism and a reckless AI arms race, Ghibli anti-war opus ‘Porco Rosso’ matters now more than ever

Arts + Culture

Susan Morris|Cinema

Dorothy and friends: Top film festival docs spotlight the women who’ve shaped media

The Observatory Newsletter

Rachel Paese|Cinema

Dread for dinner

History

Madison Jamar|Analysis

Dread for dinner: class anxiety is best served at the formal dining table

Related Posts

Arts + Culture

Dylan Fugel|Analysis

“I’d rather be a pig”: Amid fascism and a reckless AI arms race, Ghibli anti-war opus ‘Porco Rosso’ matters now more than ever

Arts + Culture

Susan Morris|Cinema

Dorothy and friends: Top film festival docs spotlight the women who’ve shaped media

The Observatory Newsletter

Rachel Paese|Cinema

Dread for dinner

History

Madison Jamar|Analysis

Sigourney Schultz is a Los Angeles–based writer and art historian whose work explores diasporic memory and media aesthetics across contemporary art and technology. Her criticism and essays have appeared in Art in America, e-flux, Hyperallergic, ArtAsiaPacific, and Contemporary Art Review LA. She holds an MA in art history from Hunter College in New York City. Blending personal memory with cultural critique, she writes about the expansiveness and responsibilities of our rapidly evolving digital world. Outside of writing, she spends her time wandering Los Angeles with her dog, Bacon, rewatching Studio Ghibli films, and contemplating speculative futures, both real and imagined. Learn more at

Sigourney Schultz is a Los Angeles–based writer and art historian whose work explores diasporic memory and media aesthetics across contemporary art and technology. Her criticism and essays have appeared in Art in America, e-flux, Hyperallergic, ArtAsiaPacific, and Contemporary Art Review LA. She holds an MA in art history from Hunter College in New York City. Blending personal memory with cultural critique, she writes about the expansiveness and responsibilities of our rapidly evolving digital world. Outside of writing, she spends her time wandering Los Angeles with her dog, Bacon, rewatching Studio Ghibli films, and contemplating speculative futures, both real and imagined. Learn more at