August 15, 2025

GenAI art is enlivening the search for Mexico’s disappeared

Families who’ve lost loved ones to the country’s decades-long Drug War are turning to an unlikely source to reenergize search efforts: ‘Ghiblified’ AI art.

Worn clothes strewn across the floor. A notebook with the nicknames of suspected (unwitting) recruits. Three crematory ovens. These were among the artifacts discovered by a search team who entered Izaguirre Ranch in Jalisco, Mexico, in early March looking for their missing loved ones.

Following an anonymous tip, a collective of families known as the Guerreros Buscadores (“Seeker Warriors”) sifted through the dirt and uncovered evidence of tactics attributed to Jalisco New Generation Cartel, including forced recruitment, training, and alleged murder.

This wasn’t the country’s first revelation of a suspected cartel “extermination site.” Though the Mexican government officially denies the existence of such sites, Ibero-American University has found and documented seven extermination sites and six crematoriums between 2020 and 2024, along with more than 3,000 clandestine graves since 2006. Media reports allege that victims are lured to these locations through fake job ads, then detained and, in some cases, tortured and killed if they fail to comply with orders. Unlike previous discoveries, however, the Izaguirre Ranch revelation gained widespread attention, largely due to the personal effects found there — wrenching visuals that were soon radiated far and wide by an unlikely source: AI-generated videos in the style of Japanese animation house Studio Ghibli.

‘People are afraid’

At the time of publication, Mexico has officially recorded over 132,000 “disappeared” persons, those considered lost to the country’s broader pattern of criminal violence abetted by state actors since 2006, when former President Felipe Calderón took office and ratcheted up the so-called Drug War. But because disappearances often occur with the direct or indirect involvement of government agents, the true number of disappeared is thought to be far higher. And in this climate of terror and distrust, the hundreds of grassroots search groups composed of families — often mothers — looking for their missing are left with scant systemic or social support outside their self-organizing collectives.

“You knew it was happening, but nobody talked about it,” says Claudia Rodríguez, founder of the feminist collective Colectiva Hilos, which uses art to spread awareness of the crisis. “The searching mothers [told] us that they felt very alone in their struggle because people are afraid. People think that if they get closer, they will be at risk of having a family member disappear too, or even themselves. So nobody comes closer, not even to the demonstrations.”

GenAI art might be changing that.

As Mexicans awaited an official response to the Izaguirre Ranch findings, a trend was sweeping social media, with users generating “Ghiblified” versions of everything from selfies and personal videos to iconic memes and political photos. Before long, images and videos surfaced resembling those that Guerreros Buscadores had posted to Facebook.

One video, showing the mothers searching the ranch, quickly surpassed half a million views on X, breathing new life into a movement that’d long been suffering from desensitization and demobilization after decades of violence. In comparison, social posts featuring a missing-person poster rarely get more than 50,000 views, and only when shared from a high-profile account. The jarring contrast of the whimsical Ghibli aesthetic and the devastating reality it depicted drew in a public that might not normally be paying attention.

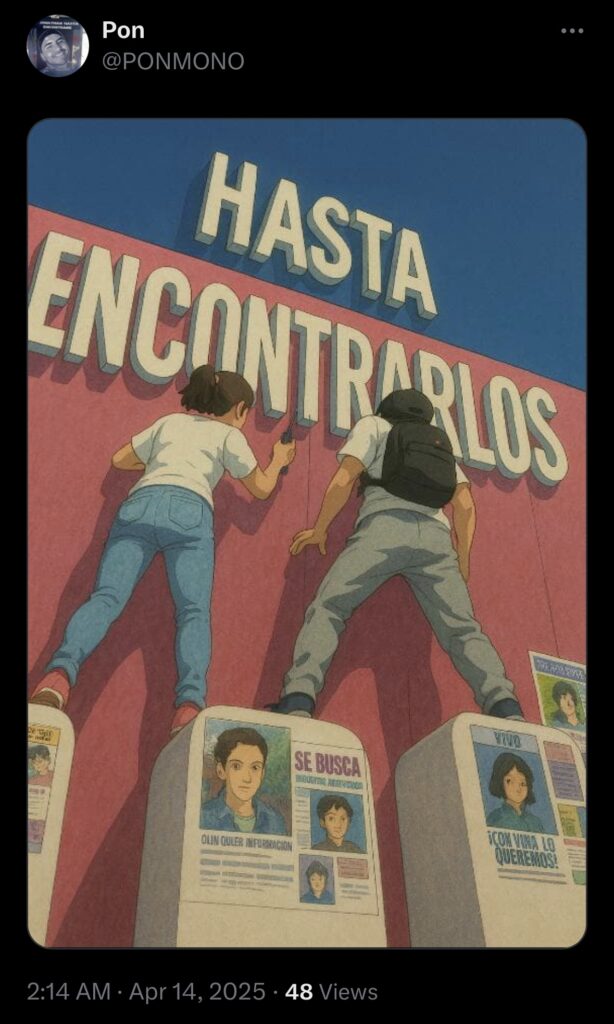

One Ghiblified image creator is Luis Alfonso Serratos, the brother of Jonathan Emmanuel Serratos, who disappeared in 2022 in Guadalajara, Jalisco. Serratos’s image portrays him carrying a backpack and hanging missing-person posters — an activity search groups undertake weekly across the city to supplement their search for mass graves.

The Ghiblified image “felt emblematic,” says Serratos. It’s more permanent than his physical posters, which are often ripped down within a day, something he worries is the government’s doing. “So I thought, ‘At least here, they can’t remove this one.’”

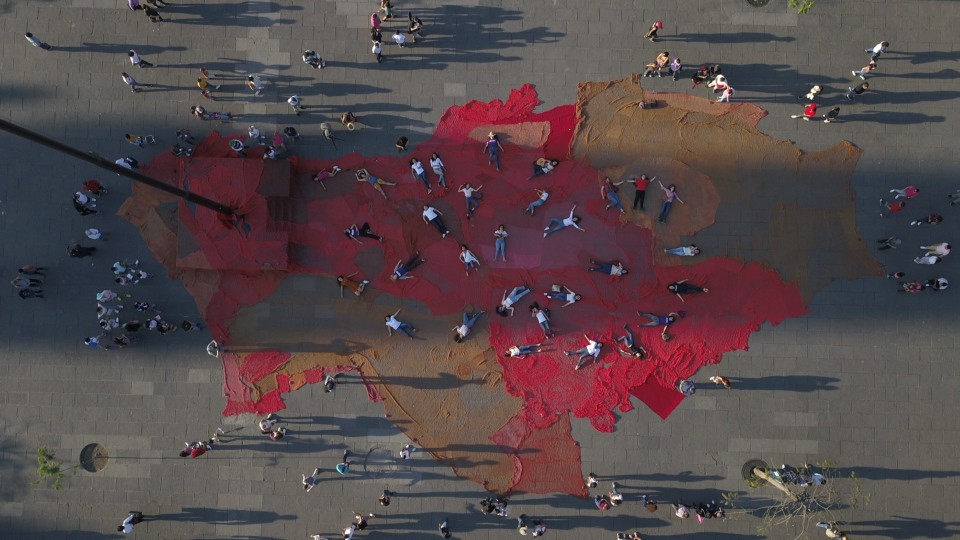

Though the medium and reach of Ghiblified visuals are distinctive, art has long been a powerful tool for raising awareness of the disappearance crisis. Colectiva Hilos’s Sangre de mi sangre (“Blood of my blood”) project involves public weaving sessions in Jalisco and other states, in which participants use a long red textile to honor Mexico’s victims of disappearance and femicide. This action has resonated not only with victims’ families, but also with hundreds of volunteers who come together to find solidarity and a space for collective healing and agency. The act of weaving has become a crucial element of sustaining shared memory, and its reach now extends to more than 10 countries. The experience is designed to “be friendly,” says Rodríguez, so that people don’t “feel threatened” and scared to join.

‘Contemporary languages’ make people pay attention

“Threatened” is the operative word when analyzing tools used to raise awareness about disappearances, as threats are frequently used to spread terror and fear among communities, and to deter them from mobilizing. As genAI is increasingly known to exploit workers and damage the environment, can we tolerate its use for raising awareness and reanimating the public about human rights violations?

Some of those closest to the matter say we must.

“These are the contemporary languages, and we have to be up to date in terms of communication so that people pay attention,” says Rodríguez.

Collectives are constantly seeking new ways to highlight the gravity of disappearances. And compared to the controversial practice of sharing photos or Facebook Live broadcasts featuring human remains or decomposed bodies, genAI art better preserves dignity and seems, at least for now, to stop the scroll, showing promise as a tool for keeping the search alive — the top priority for families of the disappeared.

“That’s our goal: for people to see us, to share,” without fear of interference, Serratos says. “So we can find them.”

Observed

View all

Observed

By Chantal Flores

Related Posts

AI Observer

Dave Snyder|Analysis

The identity industrialists

AI Observer

David Z. Morris|Analysis

“Suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar”: AI isn’t just imitating creativity, it’s homogenizing thinking

AI Observer

Stephen Mackintosh|Analysis

Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAI

AI Observer

Raphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

AI actress Tilly Norwood ignites Hollywood debate on automation vs. authenticity

Related Posts

AI Observer

Dave Snyder|Analysis

The identity industrialists

AI Observer

David Z. Morris|Analysis

“Suddenly everyone’s life got a lot more similar”: AI isn’t just imitating creativity, it’s homogenizing thinking

AI Observer

Stephen Mackintosh|Analysis

Synthetic ‘Vtubers’ rock Twitch: three gaming creators on what it means to livestream in the age of genAI

AI Observer

Raphael Tsavkko Garcia|Analysis

Chantal Flores is a Mexican freelance journalist investigating the impact of enforced disappearance in Latin America and the Balkans. Her debut book on the subject,

Chantal Flores is a Mexican freelance journalist investigating the impact of enforced disappearance in Latin America and the Balkans. Her debut book on the subject,