November 25, 2025

Making ‘change’ the product: Phil Gilbert on transforming IBM from the inside out

In a wide-ranging conversation with Design Observer, the architect of IBM’s “Hallmark” transformation explains why most corporate transformations fail, and why treating change like a premium product may be the only way organizations thrive in an AI-driven future.

The astonishing thing about Phil Gilbert’s new book, Irresistible Change: A Blueprint for Earning Buy-In and Breakout Success, is that it’s actually a blueprint.

“I’ve been around companies that have been going through transformations for decades, and as we all know, they almost all fail,” Gilbert told me over video call. “I thought we needed an ‘operator’s manual.’”

The gold standard for change thinking has long been Leading Change. First published by Harvard Business School professor John Kotter in the 1990s, the book has since become an internationally accepted framework. Gilbert had also read and absorbed its lessons. “But what’s been funny is, over the last 30 years, company after company, every single executive has read Kotter. They all use Kotter’s words, and they’ve all executed — in my opinion — transformation wrong.”

For Gilbert, already an established entrepreneur, his introduction to IBM in 2010 might just have been another notch for a serial “start-up guy:” a successful exit.

Instead, he stuck around to change the game.

Lombardi Software, where Gilbert had served as chief technical officer and president, was a small company with about 250 employees. It made, as he likes to say, “gorpy middleware stuff,” the kind of plain, business process management software that rarely generates much excitement, let alone fans. But Lombardi had both.

“It kind of blew IBM’s mind…[Lombardi’s] clients, even the businesspeople at our clients, were loving our software.” IBM’s customers, on the other hand, didn’t like the products and found it difficult to do business with the company. It was a predictable problem for an engineering-led culture that told customers what was coming rather than learning what they needed. And while Gilbert spoke fluent Kotter, he had also become fluent in another language: design, specifically design thinking, a customer-centric approach where change (innovation, prototyping, product development) became the product. Flipping the script to understand client needs would lead to the strong business relationships that IBM lacked, but flipping the bird to the status quo at a company that revered its own legacy was a daunting prospect.

It required a reframe.

“Change should be regarded as a high-value-add product that deserves the same levels of resource support and operational rigor as any of your top-performing products,” he wrote. (DEI and ESG practitioners, take note.)

Gilbert and his team learned to offer change as a premium service within IBM, and this is where the blueprint fully comes to life. He describes in detail how he gained credibility in stages. Then, in 2012, he and a small team launched Hallmark, an internal innovation engine (with a neutral name so people didn’t bring preconceived opinions about “design thinking” or “agile”) and its own internal brand that signaled prestige, exclusivity, and opportunity. Crucially, it was contextualized for every IBM team that came through, which required the Hallmarkers to create bespoke boot-camp experiences for the increasingly diverse array of new businesses and products coming online within a revitalized Big Blue.

“For IBM’s global workforce of almost 400,000 people across 170 countries … we reduced overall product time-to-market by 50 percent,” Gilbert writes. We reduced the average time project teams needed to align on initial requirements by 75 percent and cut the time required for product development and testing by one-third.”

Gilbert is unsparing, offering both granular details, meaningful critique, and juicy inside scoop. (Come for the searing assessment of what’s wrong with senior management, stay for the “magic people” who make everything better.)

Many things had to go right for this to work, including the (earned) partnership of then-new CEO Ginny Rometty, a longtime IBMer who had an unflinching understanding of the limits of the company’s culture and a keen sense of the opportunities that would be lost if they were unable to transform.

Gilbert touches on all of this and more in our conversation below, which has been lightly edited for clarity.

On designing change

Ellen McGirt: Why this book, and why now?

Phil Gilbert: When I first read Kotter’s Leading Change, I felt like it set the blueprint. But over the last 30 years, every executive has read Kotter, they use his words, and they’ve all executed transformation wrong.

I felt there needed to be an operator’s manual. There’s no strategy in my book. Kotter is the strategy. My book is how to execute the strategy of transformation, regardless of what the provocation is. I didn’t see that book out there, and as I consulted with clients, they didn’t either. They encouraged me to write down the stories and decisions we made at IBM to make our transformation happen at scale and stick.

EM: You’re a product guy and an entrepreneur whose smaller company was acquired by IBM. Why do you think you were tapped for this culture work?

PG: Lombardi was 250 people. IBM bought us in 2010. We were doing gorpy middleware — business process management — and yet business people loved our software. IBM had deep IT relationships but always struggled to get relationships on the business side. That blew their minds. They didn’t know how we did it, but they saw we had relationships they couldn’t cultivate. That’s what they noticed.

EM: What were you told IBM wanted to become?

PG: The remit was: make this small part of IBM look more like Lombardi and less like IBM. The tactics — bringing in designers, changing product management, moving from engineering-centric to human-centered — they didn’t know that. They just wanted our results: speed, great outcomes, and customers who advocated for us.

When we succeeded, Ginni heard the story. She became CEO and asked, “Whatever you did there — can we do it everywhere?”

EM: How did you prepare to give her the tough assessment of IBM’s culture?

PG: She didn’t know me, and I didn’t know her. She had already told her leadership team: clients don’t like our products, clients have difficulty doing business with us, and employees aren’t engaged. [Former IBM exec] Robert LeBlanc said, “I know this guy in Austin.”

So, my presentation was simple. I started with the business results: we simplified 44 overlapping products to four, reduced headcount from 1,100 to 700, took massive market share, our customers loved our software, and our employees were among the most engaged.

Then she asked how we did it, and I explained how we moved from an engineering-centered culture to a human-centered, user-centric one that listened to users and responded to their needs.

EM: You were asking IBM to rethink something they were proud of — engineering excellence. One thing you did was make the change itself the product.

PG: Yes. That was the animating premise. Ginni asked, “Can we do it everywhere?” and I said, “Let’s give it a go.” I knew most transformations fail because they’re treated as enablement. They count butts in seats. Education doesn’t change anything. They focus on individuals, but teams generate outcomes. And I had no authority — Ginni was asking me to influence 400,000 people in 180 countries.

Then it hit me: this is the same problem startups have. Nobody knows you. People have existing workflows. Mandates don’t work — compliance isn’t adoption. Startups succeed by building products people want. So, we built the transformation as a product people would willingly adopt.

EM: Do you have a process for these “aha moments” you describe in the book?

PG: I get out of my head and onto a whiteboard. I’m tactical — I list everything that needs to happen. I have to write it physically. Then I get away from it, and usually the insight comes the next day in the shower or on a walk. I’m good at pattern-matching, not memorizing details.

EM: Your audience is designers and leaders trying to find impact in their organizations. This is one of the most successful internal branding efforts I’ve seen. How did you develop it?

PG: As I thought about “product,” I thought about attributes: delightful, easy to consume, people can taste it. And one of the most important things: people have to buy it. Freemium doesn’t work in enterprise. After our first year, every team had to pay their own way.

I also realized everyone had preconceived notions about design thinking and agile, and none were good. I could either change 400,000 minds, or create a concept that meant nothing at IBM and define it ourselves. A brand. We chose “Hallmark.”

Two big unintended consequences: it freed my team from thinking this was just design. It opened us to rethinking tools, HR ladders, communications — everything.

It created demand. A velvet rope. “We’ve got this cool thing called Hallmark; you don’t have to come in.” Suddenly, everyone wanted in.

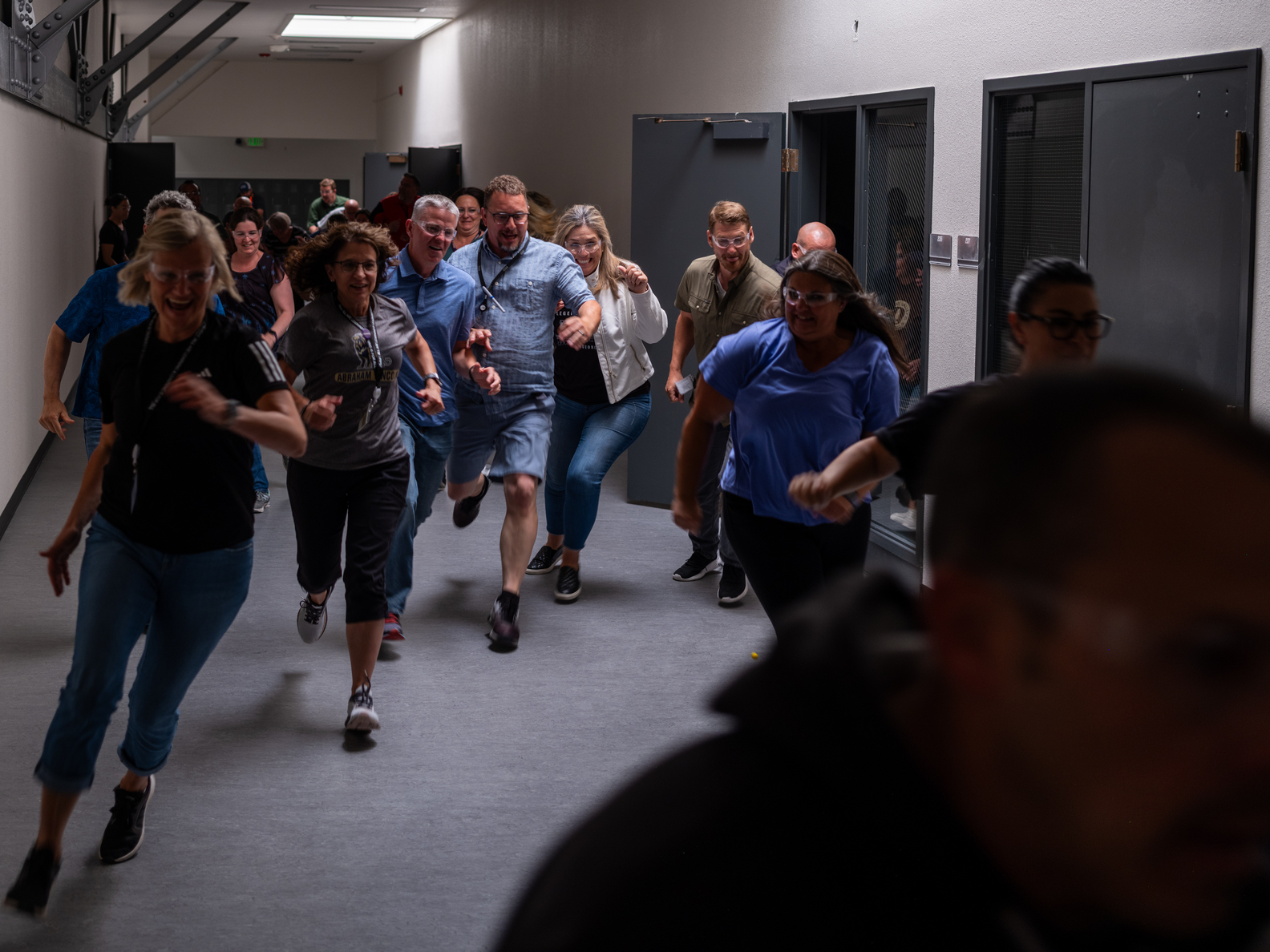

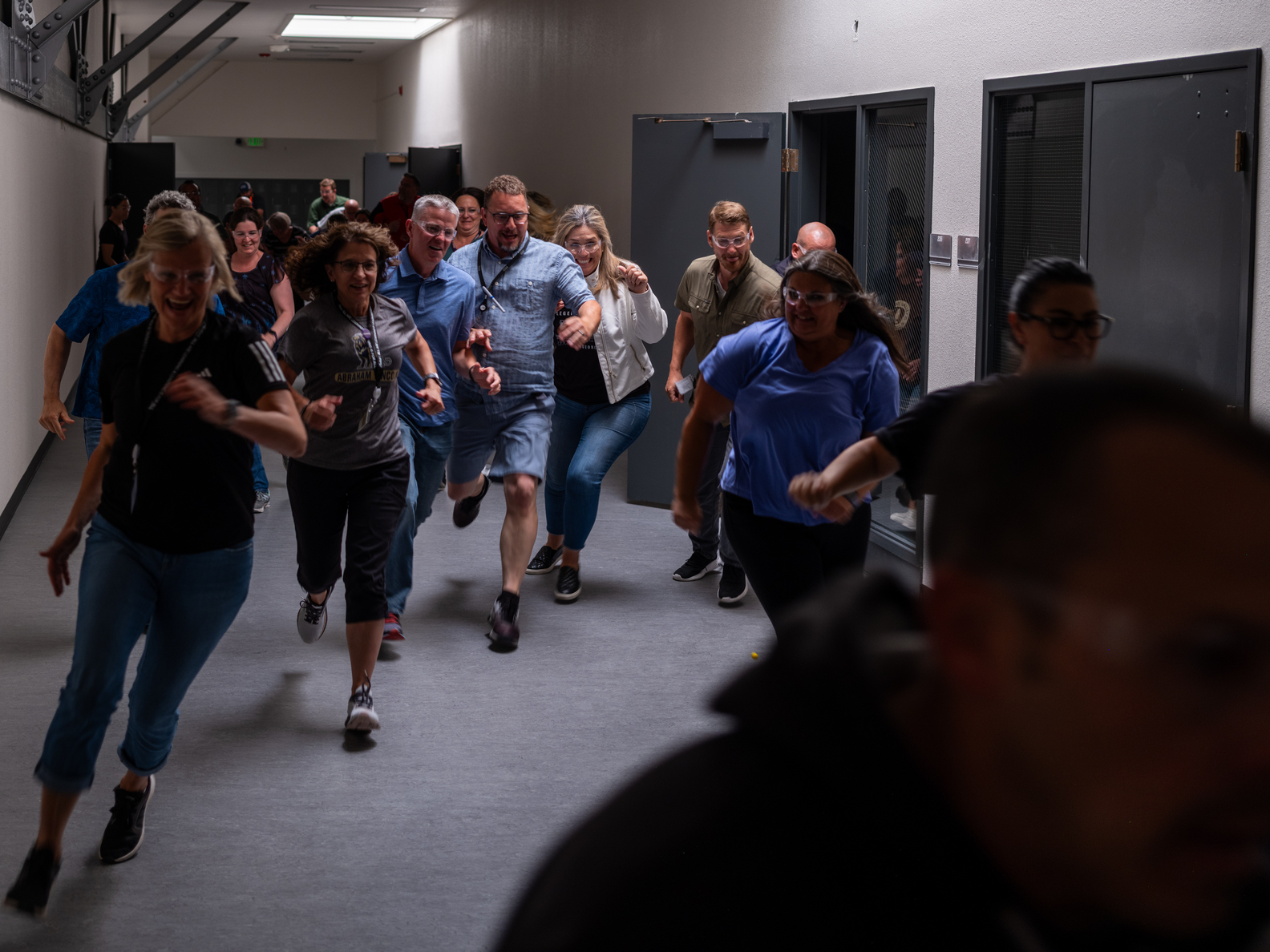

EM: On a tactical level, what was the first Hallmark bootcamp like?

PG: Every week was bespoke. We introduced new practices in the team’s context and advanced their projects further than they ever would have in that same time. That required a ton of work — we had to learn their projects fast.

On Sunday night I told my team: you thought you were in the design business; you’re in the hospitality business. They’re doing us a favor. We wanted to surprise them at every touchpoint.

IBM usually let people travel during work hours. We didn’t. We made them be in Austin at 8 a.m. Monday, which meant traveling Sunday. We wanted people to show up agitated so the skeptics would surface early. Their objections were valid — they revealed barriers we needed to fix.

EM: What was your promise to them?

PG: If by Friday at noon your project hasn’t advanced 10X over where it would have been, you can leave and never hear from us again. Nobody ever took me up on it.

I trust people. No one shows up to do bad work. If they oppose a change, either the change isn’t better, or our delivery is flawed. On my team, it was forbidden to say, “They just don’t get it.”

EM: You connected this to inclusion — how different things would be if inclusion had been rolled out with the same mindset. Is there a way to reframe belonging and inclusion using this approach?

PG: I believe that 100%. There are no mandates. Only opportunities.

If DEI programs are rethought and reframed around opportunity — “here are the tools, here are the ways of working, come in if you want” — people come in. We started an effort around equity in design in 2020. It was about finding the best people who weren’t being found. Not diluting the merit pool. We never had a meritocracy in the first place. This approach can be used in any context — even to implement bad policy better.

EM: As Hallmark grew, how did you measure its impact on IBM overall?

PG: We created a formula: culture = people + practices/tools + places. Everyone on my leadership team had goals tied to those three. We counted certified people, new tools adopted, and environments transformed. Even though nobody reported to me, Hallmark added headcount by certification and practice adoption. Headcount gives you power — and power gives you resources.

We reported these metrics every quarter to the CEO and top three levels. We visualized team composition by level and discipline, showing leadership gaps. Hallmark became a trusted source of operational truth they couldn’t get anywhere else.

EM: Middle management — well, managers — is my favorite subject. What made middle managers resist at first, and how did you help them?

PG: Most programs teach middle managers the same thing the teams learn. That’s fine, but inadequate. Their real problem is that they have two teams working in different ways and no framework to reconcile their artifacts.

For example, if I’m used to counting lines of code or user stories and now you’re doing journey maps and low-res prototypes, I think you’re 0% complete. We hadn’t given them a framework to translate. Once we did, everything changed. You don’t train them on the thing; you train them on how to manage the thing.

EM: During this time, IBM was expanding into cloud, analytics, AI, Weather Channel, cybersecurity. How did your team support such a range?

PG: Hard work. Then we saw patterns. Some people emerged — magic people. Designers, engineers, introverts, extroverts, didn’t matter. If a team had one or two, they performed extraordinarily. Same time, The Captain Class came out. We created heuristics to discover magic people and built a coach network. That network became the backbone of scaling. They volunteered to help other teams, run workshops, and intervene when needed. They scaled us.

EM: Should people try to become magic people?

PG: You can’t train them. Some people naturally do it. You can identify them early. We put guardrails around overuse. They still did their day jobs; the network supported itself.

EM: You hit 5,000 people in 20 months. How did you scale to tens of thousands?

PG: [IBM design exec] Doug Powell said his team could get the next 5,000 in half the time. I told them we needed to reach 50,000 in the next year. They thought I was joking. But we had to scale without violating the principle that training isn’t enough; it had to be experiential. They figured it out. By the end of the next year, we had over 55,000 people delivering outcomes using these practices.

EM: As Hallmark folded into IBM and design thinking fell out of fashion publicly, what happened?

PG: When someone does something well, and it becomes popular, people copy it and turn it into a checklist. It’s not a checklist. It’s a mindset. At IBM, people show up human-centered, user-first, interdisciplinary, iterative. Whether they call it design thinking or not, it has won.

We’re in a technical disruption cycle. AI requires integration, tooling, data protection — it’s expensive. Companies shift investment. But in the post-integration period, the value will come from people who imagine multiple futures, do divergent thinking, and understand users.

We’ll live in a world where executing artifacts approaches zero cost. Today, teams prototype maybe two or three futures. Imagine prototyping a dozen, a hundred, a thousand in days. That’s the opportunity. Team ratios will shift to value imaginative skills.

EM: What’s next for you?

PG: I’m on the book junket for the rest of 2025. Then consulting again. Helping companies navigate AI and get teams working in new ways.

More like this:

Design of Business | Business of Design

Michael Bierut|Audio

S5E2: Jon Iwata

Jon Iwata is executive in residence at the Yale School of Management and a senior advisor to IBM.

Design of Business | Business of Design

Audio

The Risks of Retreating from DEI with Catalyst’s Alix Pollack & Doug Powell Redesigns Design Thinking

In a time where it’s hard to feel hopeful, a new study has left leaders who value DEI aflutter with tentative optimism. It’s called The Risk of Retreat, conducted by Catalyst and the NYU Meltzer Center of Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging, it compiled data from surveys of 2,500 employees from across the U.S. on their … Continued

Design Impact

Ellen McGirt|Books

No mandates, only opportunities: IBM’s Phil Gilbert on rethinking change

Ellen McGirt interviews Phil Gilbert on IBM’s design-led transformation and why treating change as a product—not a skill—shapes the future of AI and creative work.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Ellen McGirt

Related Posts

Design Impact

Alexis Haut|Education

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

A quieter place: Sound designer Eddie Gandelman on composing a future that allows us to hear ourselves think

Related Posts

Design Impact

Alexis Haut|Education

‘Thoughts & Prayers’ & bulletproof desks: Jessica Dimmock and Zackary Canepari on filming the active shooter preparedness industry

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

Beauty queenpin: ‘Deli Boys’ makeup head Nesrin Ismail on cosmetics as masks and mirrors

Design Juice

Rachel Paese|Interviews

Ellen McGirt is an author, podcaster, speaker, community builder, and award-winning business journalist. She is the editor-in-chief of Design Observer, a media company that has maintained the same clear vision for more than two decades: to expand the definition of design in service of a better world. Ellen established the inclusive leadership beat at Fortune in 2016 with raceAhead, an award-winning newsletter on race, culture, and business. The Fortune, Time, Money, and Fast Company alumna has published over twenty magazine cover stories throughout her twenty-year career, exploring the people and ideas changing business for good. Ask her about fly fishing if you get the chance.

Ellen McGirt is an author, podcaster, speaker, community builder, and award-winning business journalist. She is the editor-in-chief of Design Observer, a media company that has maintained the same clear vision for more than two decades: to expand the definition of design in service of a better world. Ellen established the inclusive leadership beat at Fortune in 2016 with raceAhead, an award-winning newsletter on race, culture, and business. The Fortune, Time, Money, and Fast Company alumna has published over twenty magazine cover stories throughout her twenty-year career, exploring the people and ideas changing business for good. Ask her about fly fishing if you get the chance.