June 14, 2018

Red Light, Green Light: The Invention of the Traffic Signal

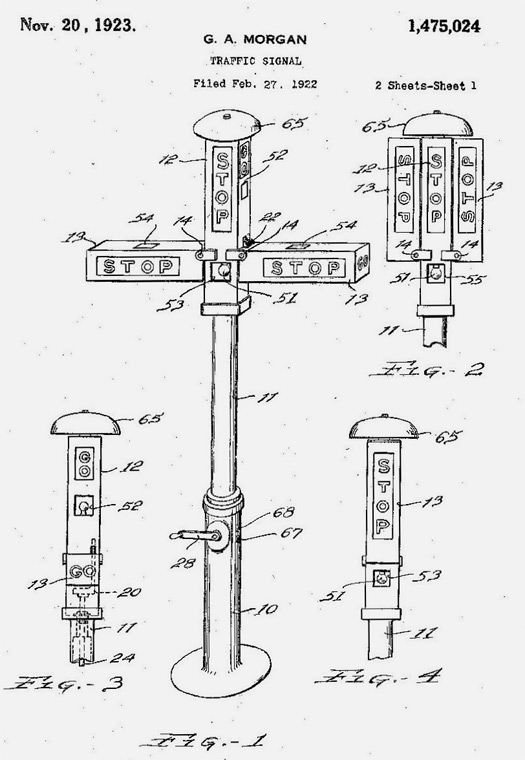

The traffic signal was first invented in 1912 — by a Detroit policeman named Lester Wire — as a two-color, red-and-green light with a buzzer to warn pedestrians ahead of the impending transition. In 1920, this basic design was modified (by another policeman named William Potts) to include the tri-colored red, amber, and green lights widely used today. This simple, three-color icon has endured for nearly a century with relatively little change, save for the incorporation of modern technologies such as automatic timers, diode lights and motion sensors. The core of the three-color traffic remains true to the initial vision of two smart American policemen.

At the beginning of the 20th century, automobiles were just beginning to gain popularity in the streets of Detroit (where Potts worked) and traffic was becoming much busier as a result. Cars were relatively new and there were few rules at that time governing their use in the streets. The initial idea for the traffic light came from Potts’ experience working as a police officer directing traffic, and several elements contribute to the success of his design.

First, Potts design chose colors that are psychologically associated with the message they are meant to transmit. Red is classically seen as a color representing danger or caution. (There are countless phrases and idioms that use “red” as a message of the bad or unknown — “in the red,” “seeing red,” and “red herring,” among others.) Green, on the other hand, is a reassuring color in most cultures — the color of nature and growth; of harmony, freshness, and fertility. Green has a strong emotional correspondence with the idea of safety, and was intuitively chosen to guide pedestrians responsibly through an intersection. Second, the traffic light could be counted on to communicate with multiple cars headed in multiple directions simultaneously. Potts’ design did not require any audio signals, so that wind, horns or other city noises would not interfere with the message being conveyed by the traffic control device. The four-direction design could transmit four simultaneous messages to the oncoming traffic, which was a noted improvement over the two-message maximum that a well-coordinated policeman could manage.

This post was originally published in June, 2010.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Mary Badon

Related Posts

Business

Kim Devall|Essays

The most disruptive thing a brand can do is be human

AI Observer

Lee Moreau|Critique

The Wizards of AI are sad and lonely men

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays

The afterlife of souvenirs: what survives between culture and commerce?

Architecture

Bruce Miller|Essays

A haunting on the prairie

Related Posts

Business

Kim Devall|Essays

The most disruptive thing a brand can do is be human

AI Observer

Lee Moreau|Critique

The Wizards of AI are sad and lonely men

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays

The afterlife of souvenirs: what survives between culture and commerce?

Architecture

Bruce Miller|Essays

Mary Badon received her MD at the Yale School of Medicine and and MBA at the Yale School of Management after doing her undergraduate majors in Biochemistry and Studio Art at Clark University. She is currently an intern in Surgery at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a Harvard Teaching Hospital in Boston, MA.

Mary Badon received her MD at the Yale School of Medicine and and MBA at the Yale School of Management after doing her undergraduate majors in Biochemistry and Studio Art at Clark University. She is currently an intern in Surgery at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a Harvard Teaching Hospital in Boston, MA.