Sanaphay Rattanavong|Design and Climate Change, The Design of Horror | The Horror of Design

October 17, 2025

The prepper’s palette: designing for collapse in a culture of control

From bunkers to backpacks, the visual language of doomsday prepping is designed for social dissolution. But when disaster strikes, it’s not the trappings of rugged individualism that will save us; it’s radical interdependence.

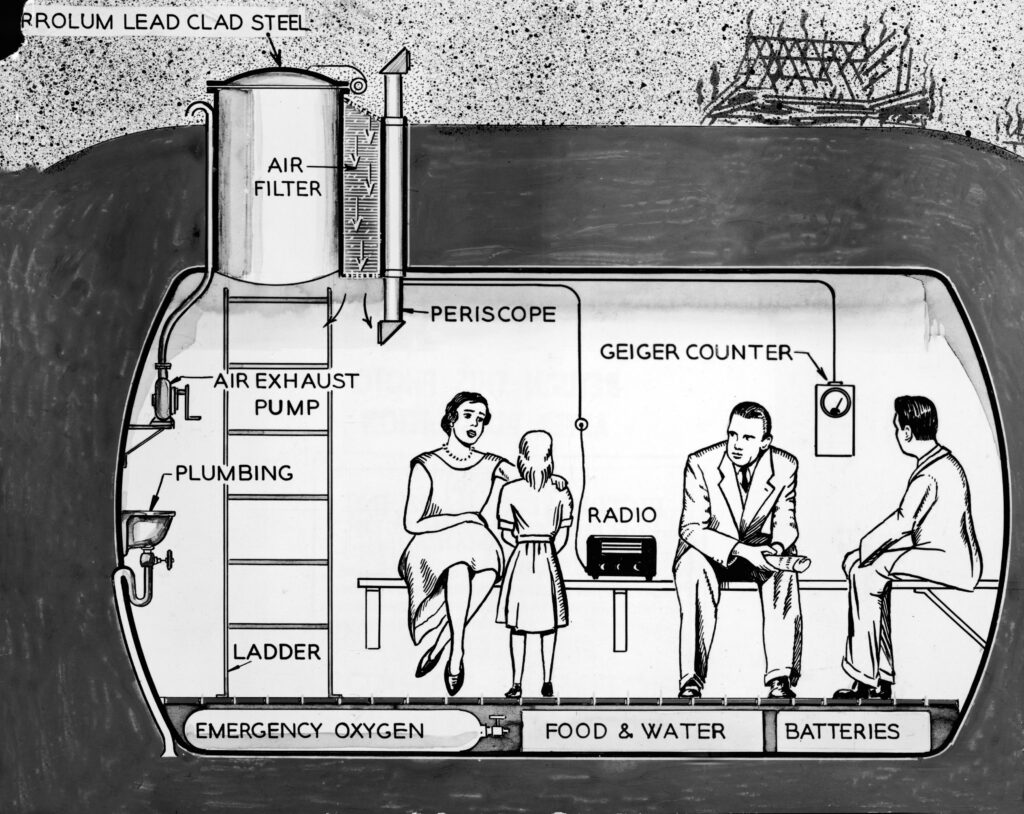

We recognize the architecture of a doomsday bunker instinctively from decades of horror and sci-fi entertainment. In 1968’s Night of the Living Dead, we already see the proto-bunker in a barricaded farmhouse: furniture against doors, boarded windows, domestic objects as weapons. By the time The Walking Dead premieres in 2010, we’ve escalated to sophisticated walls and watchtowers, enshrining fortification as the visual marker of post-collapse safety.

As prolific as these tropes are in genre fiction, they come from real existential dread that’s launched many waves of real-world preparation for end times. Today’s iteration, “doomsday prepping,” or simply, “prepping,” hinges on a profound assumption: individual escape should be prioritized over collective resilience. From bunkers to backpacks, the practice’s entire visual language is designed for social dissolution, assuming neighbors will become enemies and social contracts will splinter.

But for all this misdirected ire, doomsday culture’s endurance and reach — both as strong as ever thanks to digital amplification — belie a horrifying truth: complex systems are fragile. From supply chain and power grid failures to societal division sown by social media, today’s designed world seems to be in disarray.

So are preppers totally wrong?

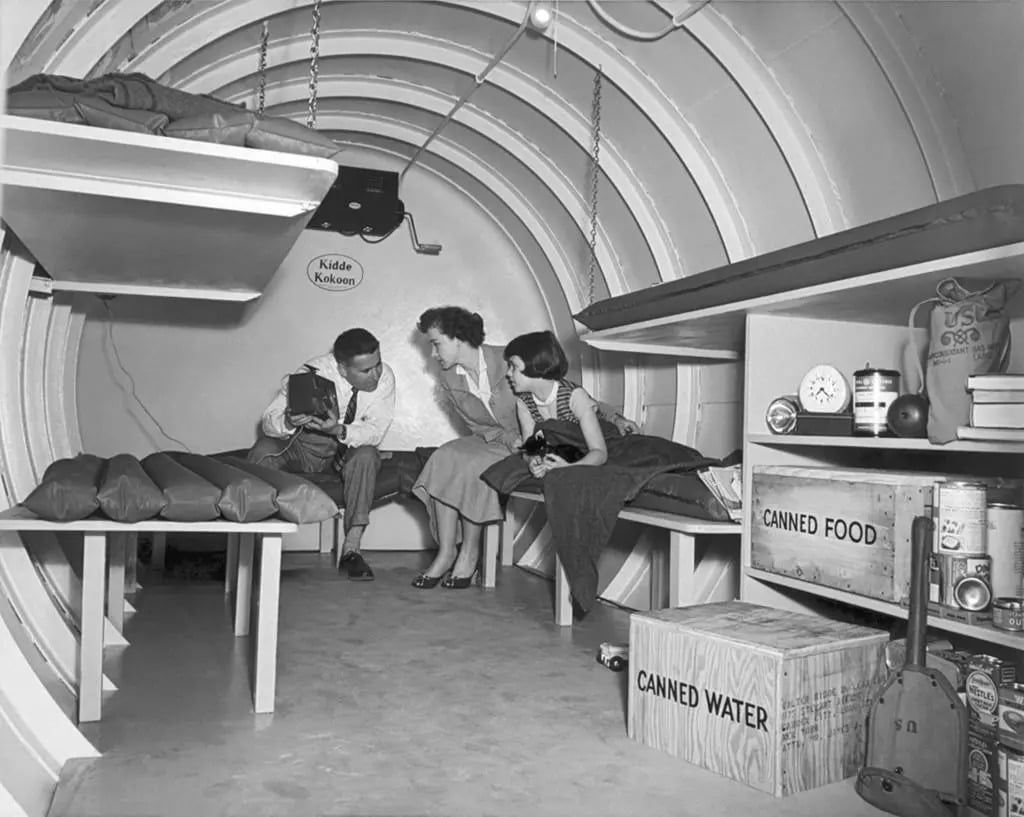

Design for individual escape

Doomsday culture, which dates back at least to medieval times, has long been a barometer for contemporary societal fears. “Retreaters,” for example, emerged in the 1950s as a product of Cold War paranoia. Their more combat-focused counterparts, the “survivalists,” surfaced in the 70s and, stoked in part by Y2K anxiety, saw their ideology calcify into right-wing extremism by the 90s. Modern-day preppers, considered by some researchers to be performing survivalism-lite, rose after 9/11.

The various facets of today’s prepper culture are saturated with visual cues, each carefully curated object serving as both a practical tool and an ideological statement.

YouTuber BlackScoutSurvival, for example, teaches nearly 700,000 subscribers to become “Hard to Kill” with “combat-ready skills, mindset training, tactical breakdowns, and unfiltered truth in a soft, weak world.” His flat lay of essential survival products presents a tension between practical use and commodity fetishism. The carefully arranged gear features military colors and patterns, traditionally associated with the type of tough, isolated masculinity the creator is promoting. The aesthetic of the gear makes viewers (and likely, buyers) feel more aligned with what they see as masculine competence.

Ron Kwok, an Everyday Carry (EDC) enthusiast with some 36,000 YouTube subscribers, communicates something different with his all-black EDC kit. He arranges each object — knife, pen, flashlight — in designer-precise grids. The matte surfaces and restrained palette communicate urban discretion and controlled readiness. This aesthetic disciplines the body through restraint, hiding tactical capabilities behind everyday objects.

Then there’s Montana Knife Company, a luxury retailer marketing blades in the hundreds of dollars not just as tools, but as “heirloom investment pieces.” These knives signal both exclusivity and prowess, transforming preparedness into heritage-based status.

Despite their differences, these aesthetics share a focus on individual escape over solidarity.

When disaster actually strikes

The preppers’ visual language teaches us a crucial lesson about design’s ideological power: every aesthetic choice says something about human nature in the midst of disaster.

But preppers get a few things wrong. First, designing a bunker that assumes your neighbor is a threat does more to create the conditions for collapse than do extreme weather patterns. And second, when disaster strikes, it’s not the consumer trappings of rugged individualism that will save you; it’s radical interdependence.

Research on catastrophic events reveals a consistent pattern: people overwhelmingly cooperate during crises.

After 9/11, for example, New Yorkers didn’t retreat to bunkers. They instead coalesced into spontaneous evacuation and aid networks. Local businesses opened their doors to provide shelter for stranded strangers, blood donation lines stretched across city blocks, and neighbors directed each other away from danger when cell networks failed.

During COVID lockdowns, grassroots mutual aid networks sprang up across North America, coordinating grocery and medicine deliveries for vulnerable residents throughout neighborhood pods. Community fridges appeared on stoops. Online spreadsheets mapped needs to resources, and chalk signs on sidewalks spelled out directives to “call this number if you need help.” These networks operated according to principles of abundance rather than scarcity, emphasizing visibility and accessibility over secrecy and hoarding.

Contrary to the dominant cultural messaging of prepping, the “every person for themselves” scenario exists more in Hollywood disaster films than in actual emergencies. Panic is rare. Mutual aid is common. Social bonds strengthen, rather than dissolve, under pressure. Ethnographic research reveals that even preppers themselves increasingly recognize that meaningful resilience depends on collective action.

It’s a choice to design for a future of cooperation and trust, rather than the one that insists on going it alone. It’s possible to acknowledge systemic fragility without adopting an aesthetic that shirks social bonds. There’s even been a rise in recent years of left-wing preppers bracing for climate emergencies, political unrest, or systemic collapse with aesthetics and practices that prioritize mutual aid, visibility, and community stockpiles. It just goes to show that the question isn’t whether to prepare for an uncertain future but how to do it in a way that recognizes our survival has always been inextricably intertwined.

Observed

View all

Observed

By Sanaphay Rattanavong

Related Posts

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays

The afterlife of souvenirs: what survives between culture and commerce?

The Observatory Newsletter

Ellen McGirt|Fresh Ink

What happens when the social safety net disappears?

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

Architecture

Bruce Miller|Essays

A haunting on the prairie

Related Posts

Business

Louisa Eunice|Essays

The afterlife of souvenirs: what survives between culture and commerce?

The Observatory Newsletter

Ellen McGirt|Fresh Ink

What happens when the social safety net disappears?

Arts + Culture

Alexis Haut|Interviews

How production designer Grace Yun turned domestic spaces into horror in ‘Hereditary’ and heartache in ‘Past Lives’

Architecture

Bruce Miller|Essays

Sanaphay Rattanavong is a Toronto-based writer and researcher exploring the intersections of technology, urban history, and human connection. Drawing on a background in journalism, arts, and science, his work has been supported by grants from the Walker Art Center and the Minnesota State Arts Board. Find his portfolio at

Sanaphay Rattanavong is a Toronto-based writer and researcher exploring the intersections of technology, urban history, and human connection. Drawing on a background in journalism, arts, and science, his work has been supported by grants from the Walker Art Center and the Minnesota State Arts Board. Find his portfolio at